Dear Mom and Dad,

The rich smell of freshly baked bread mixed with spiced cheese floated through the musky room and out the window into the afternoon sunshine. I looked over the crumbling dirt roads of Adishi and it was unclear which stone houses were occupied and which remained abandoned. Beyond the streets, across the valley, a fine mist rose up from the waterfall. The cat, which had introduced himself when we first arrived at the guesthouse, now slept on the porch in the shade of my pack.

Just outside of town, a lone tower of crumbling stone, about 4 stories high, looked like a monument to another world against a backdrop of rolling green hills and snowcapped mountains.

Similar towers dotted the roads of Adishi layering the town in a jagged medieval patchwork. They were known as Svan Towers and in the larger region of Svaneti, which consisted of many villages in Georgia’s mountainous North West, there are hundreds of them. Wide at their base and narrowing near their tops to a flat roof, they seem to grow right out of the bedrock of the towns they occupy. Originally, the Svan towers were built to shelter single families and their livestock from marauding war bands because the ground was too uneven to support large defensive walls. However, now they’re only a reminder of the generations and generations that have called the region home over the centuries.

Our guidebook[1] had told us that more and more families were returning to Adish. A well know trekking route – the four day Mestia-to-Ushguli route – passes right through the town and is walked by an increasing number of tourists each year. This influx of foreign money means that it’s once again possible to earn an income in the valley.

Travelers are drawn, like bees to a flower, to the region’s Svan towers, and though a cynical mind could describe them as tourist bait, I don’t think the towers deserve to be demeaned in such a way. They were built to protect their inhabitants and they still do. It’s just that these days, the best means of protecting the people of the village is by attracting visitors, not repelling them. And although the picturesque image of their stoic stance alone could entice a visit to the region, I believe there is more to the towers than just a pretty exterior.

Molly and I spent four days hiking among the valleys, the ridges, and the towns of Svaneti and in that time I noticed something unmistakable; an aura surrounds the Svan towers, an energy that seems to channel the very spirit of the great mountains surrounding them.

Now, perhaps this is just their looks playing tricks on a tourist’s mind, but such an explanation feels shallow. And as we hiked, I would come to find at least one local who seemed to share a similar impression of the mystic Svan towers.

…

The afternoon was growing late and if we wanted to reach the river’s edge by nightfall, we would have to cover six miles on foot in just a few hours. The rich, breaded, spiced cheese we had for lunch was beginning to work its wonders and we were able to keep an energetic pace when we started out along the road from Adishi. A cool wind parted wildflowers lower in the valley and brought with it a robust smell of earth and grass. Cows, returning from the flat pastures by the river, passed us in single file, the bells around their necks ringing as they lumbered from side to side. Descending along the valley wall, the road was relatively smooth and our gaze was free to jump from the silty churning waters far below, to the cliff faces of snow and slate and gravel above.

As the sun inched below the higher peaks at our backs, the valley bent around a ridge and revealed a colossal glacier at its end. Millions of tons of ice lay wedged between a pair of jagged peaks that rose over 10,000 feet. The glow of fading light turned orange-red and set the snow ablaze. Our path came to the riverbank just below the glacier’s foot.

There was no bridge across; we would need to wade through the current in order to pick up the road on the other side. We had no way of telling how deep the river ran. Overnight the glacier would slow its melt and the river would have less to drink, shrinking in size. But at that moment, the waters were violent and it looked like they’d swallow you up just as soon as both your feet were wet.

We made camp in a patch of grass among a birch forest. The water for our pasta dinner boiled as the last light of day faded and the air grew cold enough to demand our jackets be taken out. As the colors of twilight passed away into a starry night and our conversation became quiet, I took another look at the mass of rock and ice pilled nearby. I was struck by the feeling of its presence. It was subtle at first – a vague energy somewhere in the ether. But as the echoes of rushing water filled the air around me, I focused my attention and conceived of it: a looming mass of energy stored among the cracks and fissures of tons and tons of ice so vast that it needed mountains to be contained. The thought of the glacier as a whole, unknowable in its entirety, dwarfed my sense of being and I grew small in its presence. At the slightest trigger, its stores of raw force could be unleashed upon the valley. I, Molly, the trees, the rocks, the camp, all of it would disappear in an instant like so much dirt being kicked off the underside of a boot.

In a strange sense, the violent vision was comforting. I thought of how powerless I was in the glacier’s presence and all of a sudden, the burden of self-preservation that normally irritated the back of my mind was silenced. I offered up my remaining fears at the altar of the ice wall, if only just for the evening.

All night, I could hear the glacier’s river wearing down the boulders around me.

…

At first light, we broke camp. And before even boiling water for our coffee, we set off to find a crossing point on the river. When we arrived, it didn’t look much better than it had in the dark. The current was still loud as it battered the rocks, and the silty grey water still gave no clue as to it’s depth. We prodded the river with our trekking poles and found stones just a couple feet below the surface. But further out, there was no way of telling how deep the floor of the river may sink.

I hesitated. Other tourists had mentioned that locals from the village would come out each morning with horses and offer passage to paying tourists. Perhaps it was safest to wait. If the water pushed you off your feet, you’d be 100 yards downstream and your innards would decorate the rocks before you’d have the chance to call for help.

But before I could suggest otherwise, Molly had stripped her boots and socks, laced up her sandals and, plotting a path with her trekking poles, ventured into the water. Within a few steps she sunk knee deep and the mountain-fed force surrounded her legs. Inch by inch she continued, feeling out one foothold and then the next. At one point her pole slipped and it looked like she was losing her balance. I could do nothing but clench my jaw as I watched from shore. But with one heavy step, she plunged her leg waist deep into the grey abyss and regained her footing. Then, with each confident stride, the water receded lower and lower down her legs until at last she stepped free from the current and onto dry land.

“how was the water!?” I strained to shout over the rush of the current.

“Fucking cold!”

The path was blazed and now, for a good number of reasons, I couldn’t wait for the local horseman to whisk me across. As I changed into my sandals, the rocks along the bank were icy to the touch. Then, clutching my poles, I splashed into the water. Waves of adrenaline shot from my feet through my body and before I could get ahold of my senses, anything submerged below the surface was numb.

By keeping thee points of contact with the floor of the river at all times, I moved slowly and retraced Molly’s route as best as I could. Though my legs were numb, I could still feel the force that pushed against them. The river amounted to a mere trickle of the masses of energy stored in the ice above, and even this miniscule leak assaulted my thighs with the force of a great maelstrom. If my thin tooth-pick legs had given the current a wider surface to press against, it surely would have snapped them. Each time I lifted a foot, I wrestled with the glacier’s water for control over its movement and it struck me that this particular glacier was only one of hundreds in the Caucasus mountain range and the Caucasus mountain range was only one of thousands of mountain ranges on earth.

“You alright out there!?” Called Molly, raising her voice.

“I sure am! Water’s not so bad once your legs go numb!”

I continued to move up the bank, one limb at a time and when I emerged, the sunshine soon awoke the feeling in my legs. We boiled water for coffee right there on the shore and not long after, assumed new roles as river guides to help the half dozen or so other tourists who followed us across that morning.

The path beyond the river wound over streams, under snowy peaks, through fields of grass and wildflowers, and between villages of ancient stone. All throughout the valleys, I felt the gaze of the Svan towers either beside me in a village or far away on a hillside.

After a long day of trekking, we reached the village of Ushguli with a few hours of daylight left.

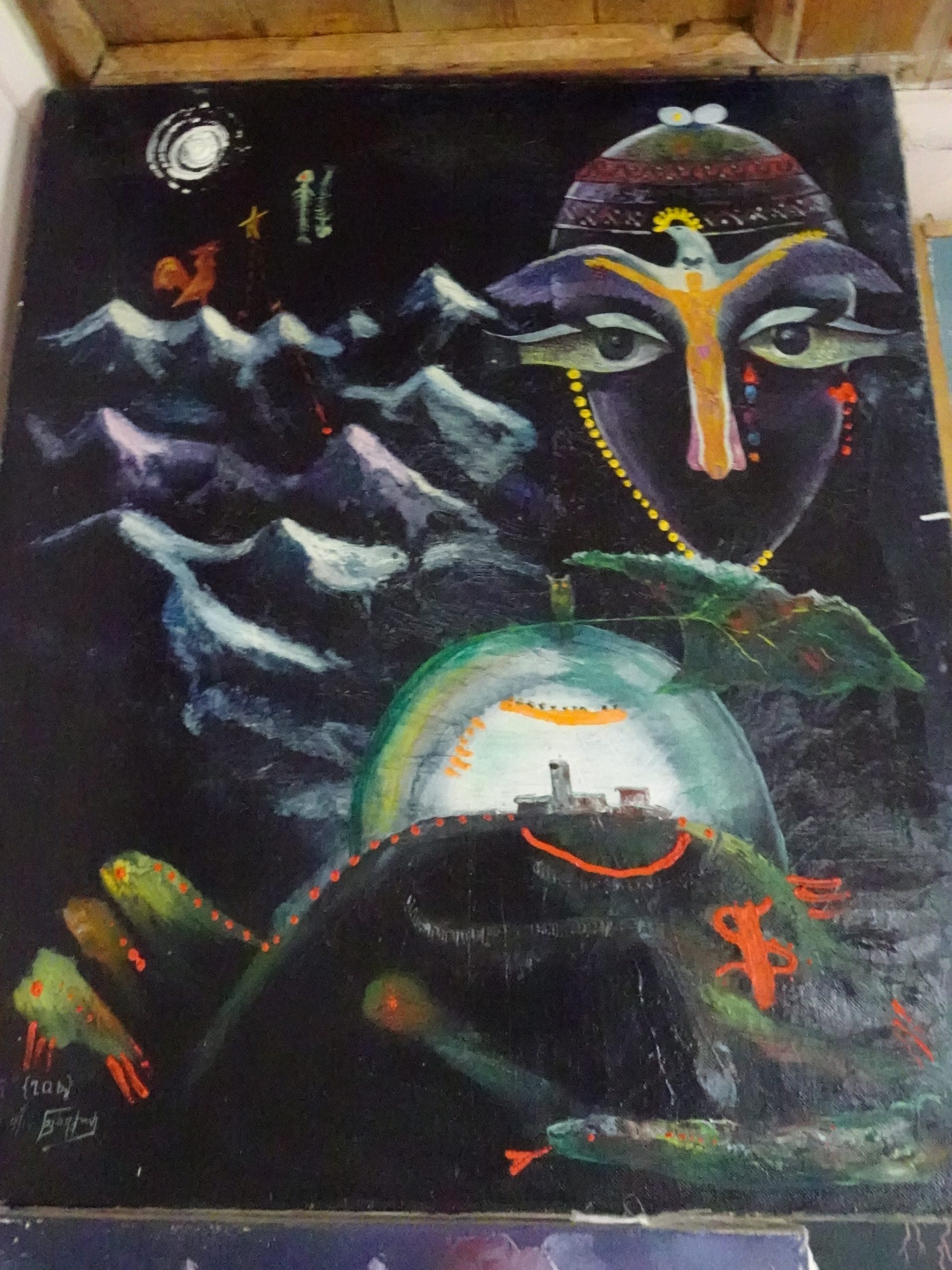

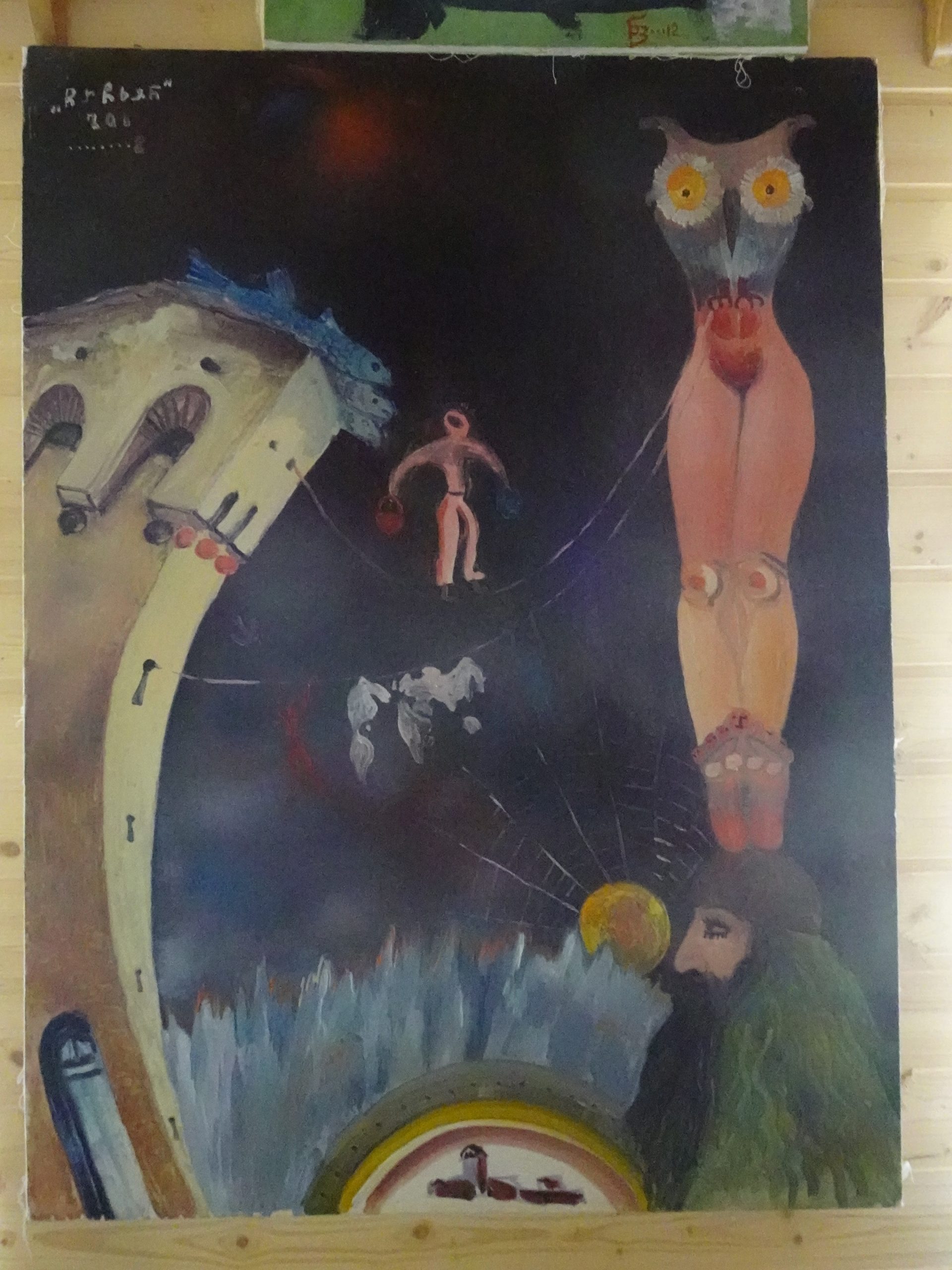

We were the only guests at Guesthouse Gamarjoba that night. The experience reminded me of staying at an aunt’s house; our host, a sturdy, middle-aged woman in a blue blouse, made it clear that this was as much our home for the night as it was hers. At the door, we were offered fresh honeycomb from a bucket in the yard before being shown the best places to dry our clothes and scrub away the days of dirt from our legs. However, Guesthouse Gamarjoba was unlike other guest houses in Svaneti. Upstairs, the creaky wooden floors and knotty pine walls were covered in the paintings of our host’s husband’s brother; Fridon who lived on the first floor. When we asked about him, she explained that he no longer painted.

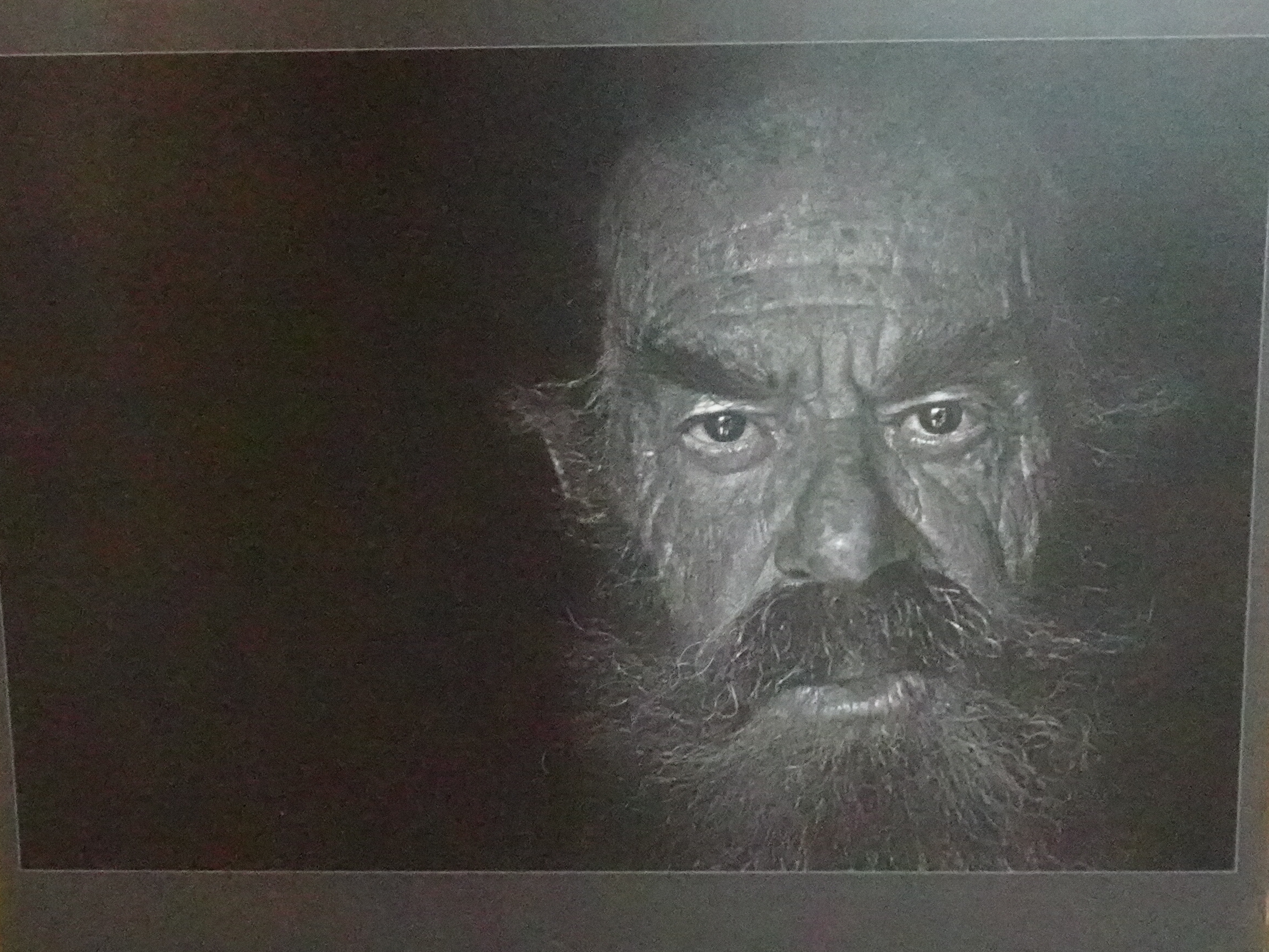

During our stay, we only caught sight of Fridon once, his face concealed behind a wild grey beard, and he did not speak to us. But he didn’t have to. His paintings spoke for him.

In dozens and dozens of images, Fridon bent and twisted Svan Towers into fantastical shapes as though the stones were supple in his hands. The towers appeared like wide grey vines on the canvas as outlined figures moved between one tower and another on strings and large red tribal masks dominated the space in between. Black backgrounds highlighted snowy mountains and joined the otherworldly images together into a vision of beyond. Svaneti’s aura seemed to flow through the brushstrokes even then, years after the paint had dried.

After a dinner of homemade soup, chicken, cucumber salad, and farm cheese accompanied by fizzy pear-flavored juice, I went to sit outside on a bench in the yard as Molly went to sleep upstairs. Stars speckled the sky. They looked like little white droplets of paint that had floated up from Friodon’s brush and settled along the roof of the world. In the yard over, a silent Svan tower cast a shadow.

Under the starlight, the stone monolith didn’t seem like a fortified building for war or a storage room for cattle, nor was its beauty limited to an image that may be re-printed in a brochure. Instead, that night, it seemed like a key to a mystical world: a portal to a place where the inconceivable energies of glaciers could be understood, a place where people lived beneath ice and rock without fear. I felt the Svan tower’s aura and although it was mysterious to me as a visitor, Fridon had seen it over a lifetime and had allowed it to be transformed within him, its being expressed through fantastical imagery.

If I looked up at the tower’s cool quiet stones, its soft wooden roof and the mountains and stars behind it, and if I closed my eyes and felt the wind’s kiss and listened to its whisper and heard the hum of running water far away, then I too could pass through the tower’s aura and into a mystical world. I could look down and see the glow of an ageless village and I could look across and see silent glaciers in their snowy kingdoms and I could feel the glacier’s gentle power as it fed the aura that flowed around the mountains and the hills and the trees and the stones and the towers of Svaneti.

I’ll write again soon,

Love Dylan

[1] Burford, Tim. Georgia: the Bradt Travel Guide. Chalfont St. Peter, England: Bradt Travel Guides, 2018.